After a long delay, owing to intrusions from the real world, I now wish to end this part of the Memory Mavens series with a discussion of perspectives and methods. For weeks I’ve ruminated over these subjects, concerned (no doubt overly concerned) that I will miss some important points. But when I do, I know I can return to them in the future. Such is the privilege of blogging.

Historical fads

1941 – 2015

Recently, while re-reading the introductory chapters to Heikki Räisänen’s The “Messianic Secret” in Mark’s Gospel, it struck me how little has changed in NT scholarship. Fads may come and go (does anyone even bother with rhetorical criticism today?), but we can always count on a sizable number of scholars to solve every problem in NT studies with a historical explanation that goes back to the “actual” words and deeds of Jesus.

William Wrede, as you will recall, addressed two problems: (1) What are the origins of the secrecy (or silence) motifs in Mark’s gospel? (2) Did Jesus think he was the Messiah, or did his disciples assign that role to him after they became convinced he had been raised from the dead? Wrede concluded that we could gain important insights into the second problem by solving the first.

By painstakingly examining each case of secrecy — silencing demons, warning people not to publicize his miracles, etc. — against contrary cases in which no such admonition is given, Wrede demonstrated that both openness and secrecy existed in Mark’s sources. He then set about to determine which traditions came first. If the historical Jesus openly proclaimed his status as the Son of God, the Messiah, the savior of Israel, etc., then it becomes exceedingly difficult to explain how the secrecy motif arose. But if Jesus did not publicly proclaim his messiahship, then we can imagine a transitional post-Easter belief (that Jesus and his disciples kept it a secret until his death and resurrection. Which is more likely?

Scholarly backlash and a volcanic Jesus

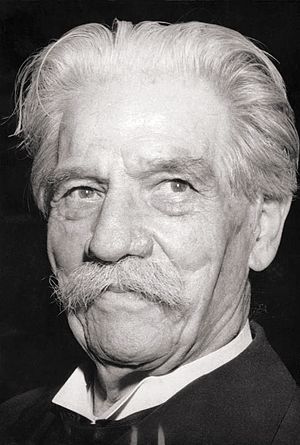

In the immediate backlash, scholars furiously accused Wrede of hyper-skepticism. As you recall, Albert Schweitzer entitled a chapter in The Quest of the Historical Jesus, “Thoroughgoing Scepticism and Thoroughgoing Eschatology.” He changed his mind, but nobody in the guild seems to care. Although scholars will pretend to have read Wrede’s Secret and Schweitzer’s Quest, the latter is the only one that’s actually on their bookshelves. And sadly, none of them seems to have caught up with the changes made in the second edition (published in 1913).

Schweitzer, along with Wrede, criticized the appalling excesses and flights of fancy which many life-of-Jesus scholars had fallen into. But Schweitzer was not immune to the allure of romantic historicization. Continue reading “The Memory Mavens, Part 11: Origins of the Criteria of Authenticity (4)”